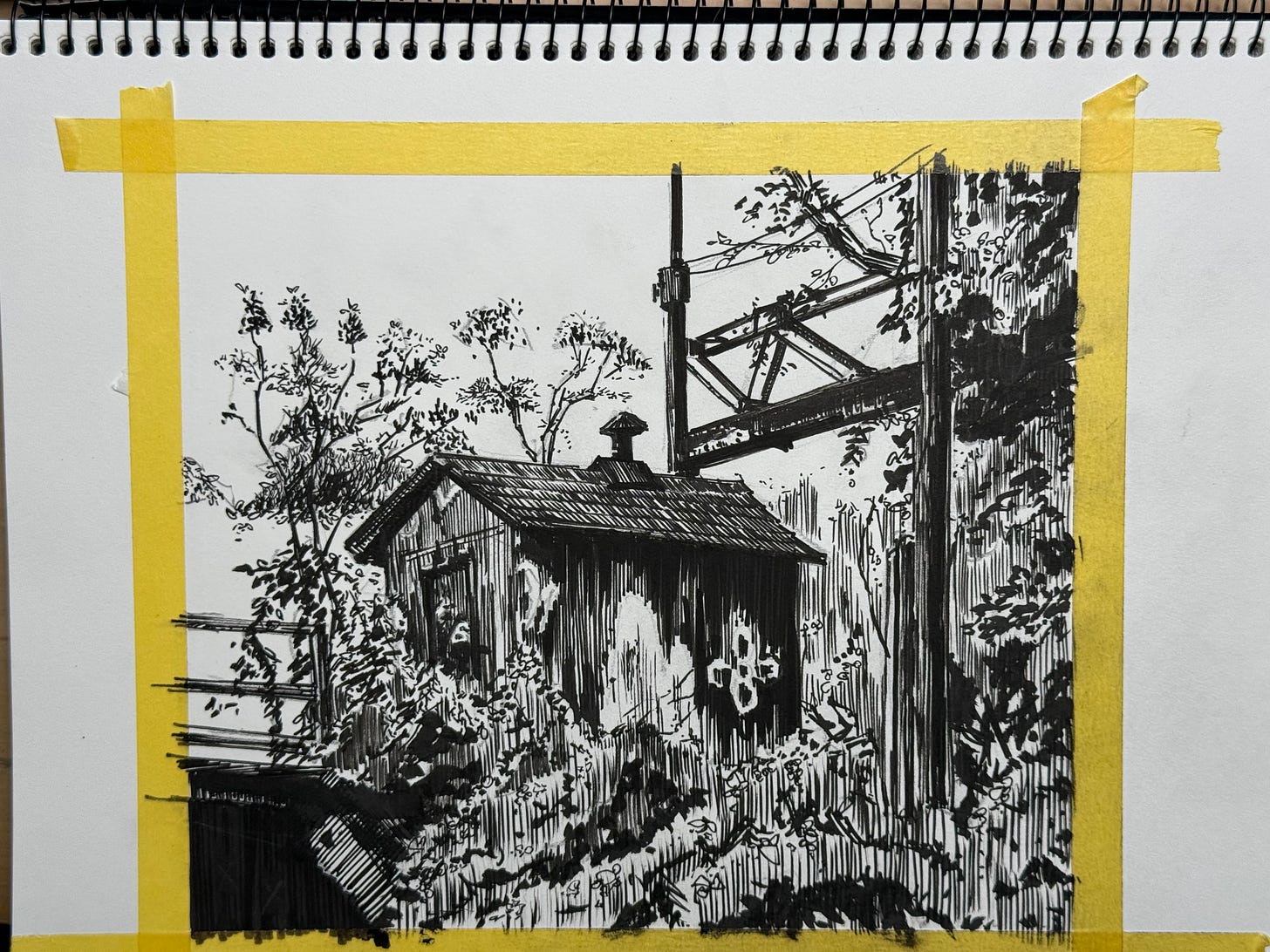

[ART] Trace, Project, or Redraw? A Guide to Moving A Sketch to a Working Surface for Paint.

Nothing says ‘artistic torment’ like taping your sketch to a window so you can trace it in sunlight while your neighbors wonder what the hell you’re doing. BTW, windows suck. There are better ways.

How to Physically Transfer a Sketch onto a Prepared Surface

Every illustrator, comic artist, and concept designer faces the same challenge: you’ve created a beautiful, dynamic sketch in your sketchbook, and now you need to transfer it accurately onto your final surface—a canvas, watercolor paper, gessoed panel, or illustration board. The right transfer method can preserve your line quality and save hours of frustration. The wrong one can leave you with a faint, distorted mess.

This article breaks down seven proven transfer methods, explaining when each works best, what materials you need, and the technical limitations you’ll encounter.

Method 1: Draw and Ink Directly in Your Sketchbook

Best for: Editorial illustration, comic pages, marker rendering, work that doesn’t require a specific substrate

The Process:

Draw your sketch in pencil in your sketchbook

Ink your line work directly over the pencil

Erase the pencil once ink is dry

Render with markers, colored pencils, or other dry media right in the sketchbook

Advantages:

Zero transfer required—no loss of line quality

Fast and immediate

No special equipment needed

Your sketch and final live in the same place

Limitations:

You’re locked into your sketchbook paper (usually not archival quality)

Can’t use heavy wet media like acrylic or oil

Difficult to frame or deliver to clients professionally

No opportunity to iterate on the drawing between sketch and final

Pro Tip: If you choose this method, invest in a sketchbook with heavier paper (at least 100 lb/160 gsm) that can handle your rendering medium. Stillman & Birn and Strathmore 500 series are popular choices for marker work.

Method 2: Visual Redrawing (No Tracing)

Best for: Artists who want to keep their hand loose, small-scale finals, learning anatomical accuracy

The Process:

Complete your sketch

Tape your final surface nearby or on an easel

Look at your sketch and redraw it freehand on the final surface, referencing but not tracing

Advantages:

Forces you to understand the structure of what you’re drawing

Often results in looser, more energetic line work than tracing

No equipment required beyond your drawing tools

Builds visual memory and draftsmanship skills

Limitations:

Requires strong observational drawing skills

Time-consuming, especially for complex compositions

Accuracy varies—difficult for technical illustration or precise likeness work

Can be frustrating if your first attempt doesn’t match your sketch

Pro Tip: Use a proportional divider or grid method if you’re scaling up significantly. Comic artist Claire Wendling is known for redrawing her sketches multiple times rather than tracing, believing each iteration improves the gesture.

Method 3: Graphite Transfer Paper

Best for: Small to medium work, smooth to moderately textured surfaces, precise line work

The Process:

Complete your final pencil drawing

Place graphite transfer paper (graphite side down) on your final surface

Place your drawing on top

Trace over your lines with a ballpoint pen or stylus

The pressure transfers graphite onto the surface below

Advantages:

Highly accurate transfer

Relatively inexpensive (Saral transfer paper is widely available)

Works on paper, illustration board, and smooth gesso panels

You can see exactly what you’re transferring as you work

Limitations:

Fails badly on heavily textured surfaces—if your panel or canvas has pronounced tooth, the transfer will be patchy and incomplete

Can create “dead” lines that lack gesture if you trace robotically

Time-consuming for large or detailed work

The graphite can smudge if you’re not careful, especially under wet media

Pro Tip: Use white or yellow transfer paper (instead of graphite) when working on dark or colored surfaces. Keep the pressure consistent—too light and nothing transfers, too heavy and you’ll emboss grooves into your final surface.

Method 4: Light Box Transfer

Best for: Moderately translucent paper (up to 140 lb watercolor paper), precise transfers, maintaining line quality

The Process:

Complete your final line work

Place your drawing on a light box

Place your final paper on top

Trace your drawing onto the final surface, backlit by the light box

Advantages:

Very accurate transfer

Fast for small to medium drawings

Preserves line quality well

Light boxes are affordable (portable LED light boxes cost $20-50)

Limitations:

Requires translucency—won’t work on thick watercolor paper (over 140 lb), illustration board, canvas, or wood panels

Difficult for large work (light boxes have size limits)

Can cause eye strain during extended sessions

You’re limited to the size of your light box

Pro Tip: If you don’t have a light box, a clean window on a sunny day works surprisingly well. Tape both papers to the glass and trace. This is how many illustrators worked before affordable light boxes existed.

Method 5: Opaque Projector (Vintage Method)

Best for: Large-scale work, murals, scaling up from small sketches

The Process:

Place your sketch in the projector

Project the image onto your final surface (canvas, wall, panel)

Trace the projected image with pencil or chalk

Turn off projector and refine the line work

Advantages:

Can scale drawings dramatically (small sketch to large mural)

Works on any surface, any size

Good for large canvas work where other methods fail

Limitations:

Opaque projectors are large, heavy, and increasingly hard to find

Expensive if you can locate one

Requires a darkened room

Image quality can be poor (dim, distorted edges)

Cumbersome to set up

Reality Check: Opaque projectors were common in the 1970s-90s but have been largely replaced by digital projectors. If you find one at an estate sale or school surplus auction, they still work—but they’re dinosaurs.

Method 6: LED/Digital Projector

Best for: Large work, scaling up, complex compositions, murals

The Process:

Photograph or scan your sketch

Load the image onto your phone, tablet, or computer

Connect to an LED projector

Project onto your final surface

Trace the projected image

Advantages:

Extremely versatile—works on canvas, wood panels, walls, any surface

Can scale infinitely (from tiny sketch to building-sized mural)

Modern LED projectors are affordable ($100-300 for decent quality)

Can adjust and flip the image digitally before projecting

Bright enough to work in ambient light (unlike opaque projectors)

Limitations:

Requires photographing/scanning your sketch first (adds a step)

Projector setup and keystoning (image distortion) can be fiddly

Need space to position the projector at the right distance

Some purists consider it “cheating” (ignore them)

Pro Tip: Portable pico projectors (pocket-sized) have gotten quite good and affordable. They’re perfect for projecting from your phone onto a canvas. Artists like Aaron Blaise and Bobby Chiu have discussed using projectors openly—it’s a tool, not a crutch.

Method 7: Camera Obscura/Lucy Drawing Tool

Best for: Observational drawing from reference, portrait work, precise rendering

The Process:

Set up your camera lucida or camera obscura device

Position your reference (or sketch) in view

Look through the optical device, which superimposes the image onto your drawing surface

Trace what you see

Advantages:

Traditional tool used by old masters (Vermeer likely used one)

Excellent for learning proportion and perspective

No electricity required

Modern versions (like the NeoLucida) are affordable ($30-75)

Limitations:

Requires practice to use effectively—the optical illusion is tricky at first

Limited to relatively small work

Works best from physical reference, not ideal for transferring existing sketches

Requires specific positioning and lighting

Pro Tip: David Hockney’s book Secret Knowledge explores how camera obscura devices shaped art history. If you’re interested in this method, his research is fascinating.

Method 8: Painting Your Line Work Directly

Best for: Loose, gestural work on canvas or panel; oil and acrylic painting; maintaining sketch energy

The Process:

Reference your sketch nearby

Use a long-handled round brush and thinned paint (burnt sienna, raw umber, or neutral tone)

Draw/paint your composition directly onto your primed canvas or panel

Work loosely and quickly—this is gesture drawing with paint

Proceed with your underpainting or color layers once the line work dries

Advantages:

Keeps your line work energetic and gestural—the brush naturally preserves dynamism

No mechanical transfer required

The painted lines integrate seamlessly with subsequent paint layers

Traditional method used by classical painters and contemporary illustrators

Forces you to commit and trust your hand

Limitations:

Requires confidence and practice

Less precise than tracing methods

Can’t easily correct mistakes without wiping and repainting

Not ideal for highly detailed technical illustration

Pro Tip: Use a long-handled rigger or round brush (size 2-6) and thin your paint to an ink-like consistency with medium (for oils) or water (for acrylics). Stand back from your canvas—the distance helps you see proportions and keeps your arm loose. This is how many classical painters worked, and it’s how concept artists like Syd Mead would establish compositions before rendering.

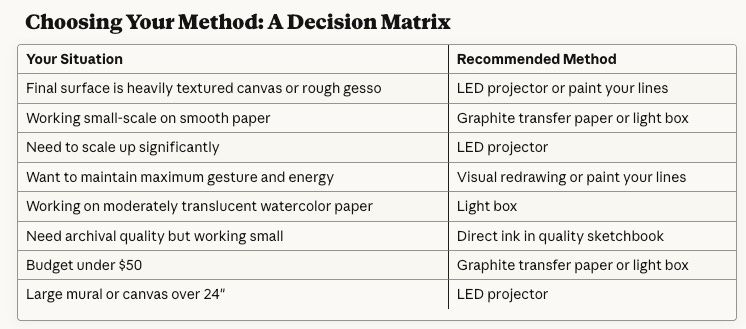

The Last Layer

There is no single “best” transfer method—only the method that best serves your specific project. A comic artist working on Bristol board has different needs than a concept artist painting on a 36” × 48” canvas, and different needs than an illustrator rendering in gouache on hot-press watercolor paper.

Experiment with multiple methods. You may find yourself using graphite transfer for tight client work, but painting your lines for personal pieces where energy matters more than precision. Many professional illustrators use different transfer methods for different projects—even within the same week.

The goal isn’t to find the “correct” method. The goal is to get your drawing from your sketchbook onto your final surface as efficiently and accurately as possible, so you can move on to the part that actually matters: rendering a compelling final image.

Your transfer method is a means to an end. Choose the one that gets you there with the least frustration and the most fidelity to your original sketch.