From Passive Description to Active Immersion: A Creative Path

I got sick of being a tool of description instead of voice of passion. My journey from design to story has been a satisfying one. Interested? It's down below.

From Architecture to Storyteller

I spent years in architecture and industrial design, focused on being descriptive. My job was to accurately convey the space or object I was designing, often for clients who couldn't visualize the final result. I used precise lines, clean compositions, and the principles of scale to help them understand what they were getting with a high degree of confidence. My work was competent, but I always felt unsatisfied.

I discovered why years later. I was convincing people what they would experience in those spaces, touching those products—trying to dictate how they'd feel in a space or interact with an object. And let's be honest, it's a tad arrogant, right?! I focused on the nouns—the things themselves—without paying attention to the verbs: the actions, emotions, and experiences that bring those things to life.

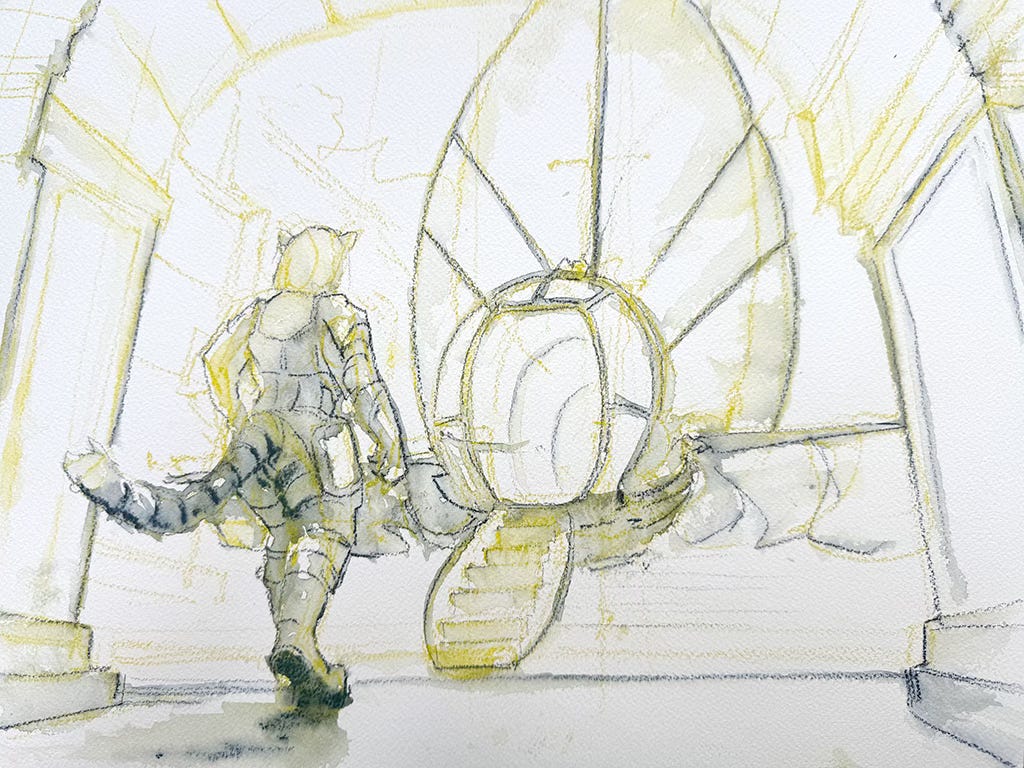

It wasn't until I began studying narrative-driven art—comic books, storyboarding, cover illustration—that I realized what I was missing. I wasn't just capturing what something looked like; I could tell a story about what was happening. That shift from description to immersion changed everything.

Descriptive Design vs. Immersive Art: What's the Difference?

In architecture and industrial design, the goal is often to describe. You're showing a space or product so the viewer can understand it logically, technically, and practically. Competent architectural designers and renderers might add scale and a few storytelling cues—maybe a figure walking through a plaza or a family gathered around a table—to hint at how people will use the space. But ultimately, it's about assuring the client understands what the object or building will look like. They hate surprises because, at this level, they're expensive!

But here's the problem: Descriptive design is passive. It tells the viewer, "Here's what you'll get." Such design doesn't make them feel more. There's no engagement or deep immersion—no invitation to enter a new world.

Immersive art, on the other hand, is active. It doesn't just describe what a thing is; it shows what's happening within that scene. It asks the viewer to engage- to wonder, feel, and imagine. Immersing the viewer comes from storytelling, action, and emotion, creating a world that feels alive.

Adding the Verb to Your Illustration

This transformation from noun-based design (descriptive) to verb-based art (immersive) is not just a shift in technique, but a change in mindset. It requires you to think differently, to ask new questions, and to approach your work with a fresh perspective. When I first began doing narrative-driven work—whether in comics or storyboarding—I took years to realize how reactive my work had been. I responded with clarity and accuracy, which was appropriate for those jobs. I'd have been fired otherwise. But I wasn't creating an experience for the viewer. (Not by a country mile. And truthfully, I wasn't being asked to do so.) But when I started to be proactive by looking for the verbs, everything changed.

Here's what changed when I began asking myself these questions:

1. What's happening in this scene?

• Instead of asking, "What does it look like?" I started asking, "What's the story here?" In a drawing of a character, what are they doing? How are they reacting to something in the environment? The moment you think about action, you move beyond static representation.

2. What are the characters doing and why?

• If I'm drawing a character in a space, I'm now thinking about their motivation. Are they climbing, resting, or searching? How do their actions inform the composition? A character's intent should guide the viewer's focus in a narrative illustration.

3. What are the reactions and emotions?

• Emotion drives the viewer's connection to the illustration. If my characters react to something—an event, another character, or an external force—it adds tension and immediacy. The synchronization between the character and the viewer creates a sense of engagement and immersion. It elicits feelings and emotions like they're experiencing what the character is feeling along with them.

4. How do I want the viewer to feel?

• This is a critical question that architects rarely consider (I know I didn't). But in narrative illustration, I ask myself, "What emotion do I want to evoke in the viewer?" Do I want them to feel excited, tense, or serene? This decision will affect everything from composition to color palette.

The Tools to Create Immersive Illustrations

There are a few tools that can help shift your mindset from descriptive to immersive. When you're trying to bring action and emotion into an illustration, you need to be deliberate about certain elements:

1. Dynamic Composition:

• Static compositions—straight-on views, centered subjects—tend to feel less immersive. Think about using diagonals, asymmetry, and foreground/background layers to create a sense of motion and depth.

2. Lighting and Contrast:

• Lighting isn't just about highlighting form—it's about setting the tone and guiding the viewer's eye. Where are the shadows? What mood does the light convey? Strong contrasts can emphasize the action and emotion in your scene.

3. Character Interaction:

• Characters in your scene shouldn't just exist in isolation. Think about how they're interacting with the environment or each other. Gestures, expressions, and body language are crucial to creating an emotional connection with the viewer.

4. Storytelling Details:

• Small details can elevate an illustration from competent to captivating. What are the objects in the background? How does the environment reflect the mood of the scene? These are the details that make an illustration feel alive.

Moving from Competent to Captivating

I've drawn thousands of competent illustrations or what designers call “renderings” that technically "work" and show what they need to show. But if I'm being honest, most stopped there. They didn't convince the viewer to enter a new and unfamiliar world. The viewer didn't come away feeling anything.

But I shifted my approach. I want my drawings and illustrations to be immersive. I want to tell stories with my work, not just describe things. Different Goal. (Getting every detail perfect ain't my jam.) I've shifted, so now it's all about action and emotion. This shift in mindset helped me, and it might help you. Start asking the questions, and see if your art transforms.

If you're anything like me, you've spent years making your drawings clear and accurate; I challenge you to think about what they’d look like as verbs instead of nouns. What's happening, and how are your characters or objects reacting? Are they emotional or passive? If not, why not? How do you want viewers to feel when they look at your work?

You don't have to make this shift immediately or at all. We need accurate and precise renderings as not everyone has the visual imagination necessary. But if you hanker for a new approach, adding action to my artworks made them feel more alive. (I like that. It’s what I’m after.)

If you have a technique for making your illustrations immersive that I missed, drop it in the comments—I'd love to learn how you do it!

Charles Merritt Houghton

20 October 2024

I only intended to illustrate a mental transition that I've made from being description-driven, which is critical and valuable, into being more interested in story-driven. Not being descriptive, for designers, is probably Malpractice. You must be visual; you must be clear to do your job. And choosing a meaningful, personal path is tough for all of us. I only hope everyone gets a clear-sighted view of their path forward as possible, given the confusion and chaos of being "in it."

Good Food for thought, this article on narrative as dynaic vs passive.

I feel You”ve covered all the points on active (immersive) narrative technique s. My only comment to add on this subject is be: genuine lto oneself, .e.g. be wary of the secuction of “group fashion”, so to speak. Ask oneself when one is alone: is that group fashion really me? Also,To have lived a bit (in the brain, or in the body) may help a bit (or not).