♦♦♦[ART] Frozen Moments vs. Flowing Time: Why Motion in Comics is Different Than Animation

Your brain processes comic and animation in distinct ways. Discover how your brain creates movement from still images versus moving images.

Animation Expresses Time; Comics Compress It

The Different Approaches to Motion in Visual Storytelling

When discussing visual storytelling with students, it's critical to highlight a fundamental distinction: Animation expresses time; comics compress it. This difference might seem obvious, but it affects how each discipline approaches movement, action, and storytelling... profoundly.

Most of us intuitively understand animation. We've grown up with it. Whether you're from the Saturday morning cartoon generation, the Pixar hegemony, or the YouTube stream-on-demand generation, animation has been thoroughly explained, dissected, and celebrated. The famous "12 principles of animation" shared by the Disney animators, Frank Thomas and Ollie Johnston, are gospel. Really, The Illusion of Life is the bible of animation as much as Understanding Comics is the bible of comics. Read both. Your life will be richer for it.

But comic art? Despite the overabundance of superheroes in popular media, the unique visual language of comics, particularly how static images convey explosive action and fluid motion, continues to feel mysterious. If animation reveals motion directly, comics can only evoke it. Artists carefully select moments, then use visual cues and artistic shorthand to bring them to life. Animation performs time continuously; comics encode it in the space of the page.

The Fundamental Difference: Expressing vs. Compressing Time

Before diving into specific techniques, let's understand the core differences in how these media handle time and motion:

Animation expresses time:

Unfolds through dozens of frames in sequence (typically 24 frames per second)

Reveals the full spectrum of movement in real-time

Controls the exact timing and pacing of every microsecond of motion

Viewer passively experiences the predetermined temporal flow

Shows motion directly through sequential change

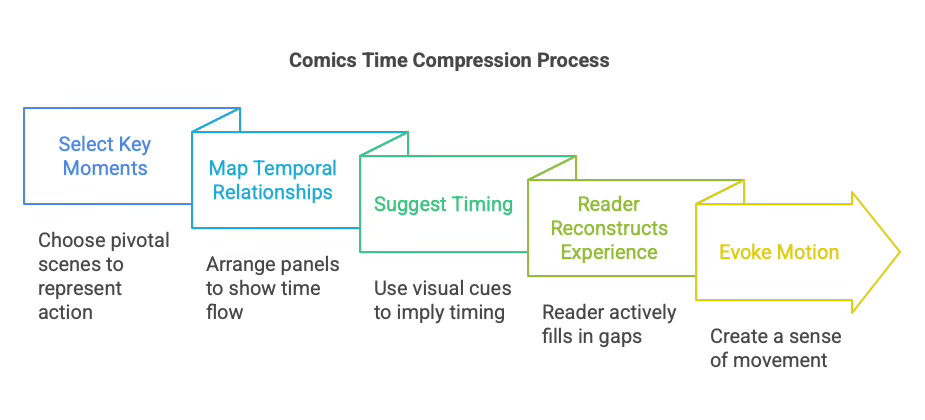

Comics compress time:

Embeds time in space through carefully selected key moments (typically 2-4 panels per action)

Maps temporal relationships spatially across the page

Suggests timing through panel size, placement, and composition

Reader actively reconstructs the temporal experience

Evokes motion through visual cues and the cognitive impulse to fill in the gaps between moments

Comic artists aren't just working with fewer frames. They express time in a totally different way. Animation unfolds in time, comics embed time in the paper, in the pages and panels, converting temporal experience into spatial relationships. Drawings readers mentally process. The "closure" that Scott McCloud describes, which I cover below, happens internally.

The Neuroscience of Comics: Closure and Gutters

Time compression in comics works because of "closure"—the cognitive phenomenon that Scott McCloud describes where readers observe parts but perceive a whole. This is how comics trigger readers' perception of motion.

The Magic of the Gutter:

The blank space between panels (the "gutter") is where readers mentally create movement and time

McCloud describes closure as "observing the parts but perceiving the whole."

This cognitive process transforms static images into perceived motion

The gutter allows comics to compress time by eliminating unnecessary moments

How Closure Works for Motion:

Reader's brain automatically fills in missing action between panels

Different panel transitions treat closure differently

Our minds are wired to complete patterns and sequences. It’s instinct. Use it or ignore it, it’s gonna happen either way.

Comics leverage this neurological tendency to create the illusion of motion.

As McCloud explains, "If visual iconography is the vocabulary of comics, closure is its grammar." This cognitive engagement is why comics can successfully compress time rather than express it fully—readers mentally reconstruct the entire temporal experience from compressed moments. It's magic. And happens in your reader's mind.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to The Invisible Thread - Making Comics by Charles Houghton to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.