♦♦ [STORY] "Natural" Dialogue in Comics Ain't Natural. It's fake as hell, but get it right, and you'll dominate the page.

In comics, talking like people talk rarely works like you think it should. Here's what to do instead. Trim like a military barber on the first day of basic training.

Capturing how people actually talk, each and every word, rarely works. Might work for the courtroom, but it doesn’t work on the page. Here's the reality.

Real conversations wander. (Squirrel!)

Comic dialogue throws punches—short, sharp, and aimed straight at the reader's gut.

Comic creators love writing dialogue that sounds real. It's how we connect with readers, express character, and pace a scene. Here's the "gotcha." Comics are not a conversational medium. They simulate speech within a rigid visual architecture. Page real estate, the surface area on your Bristol paper, is a precious resource. Guard it.

When your page gets jammed with balloon after balloon of "natural" speech, it reads as bloated, clumsy, or intolerably meandering. Don't choke out the artwork by filling all the negative space with words. Bad habit. That empty white space is the air your page needs to breathe.

Let me be blunt: in comics, dialogue isn't natural. Even Aaron Sorkin, in interview after interview, admits that his dialogue, for which he is lauded and acclaimed, is artificial as red #40 in Red Velvet Cake. His guide isn't versimilitude; it's impact and cadence; according to him, it's lyrical. His dialogue is set to a metronome; it does not imitate real conversation.

We have to adapt speech for comics. It's a compressed form. Composed, edited, and distilled into textual/visual poetry. It's the illusion of real speech, sculpted for maximum impact in minimum space.

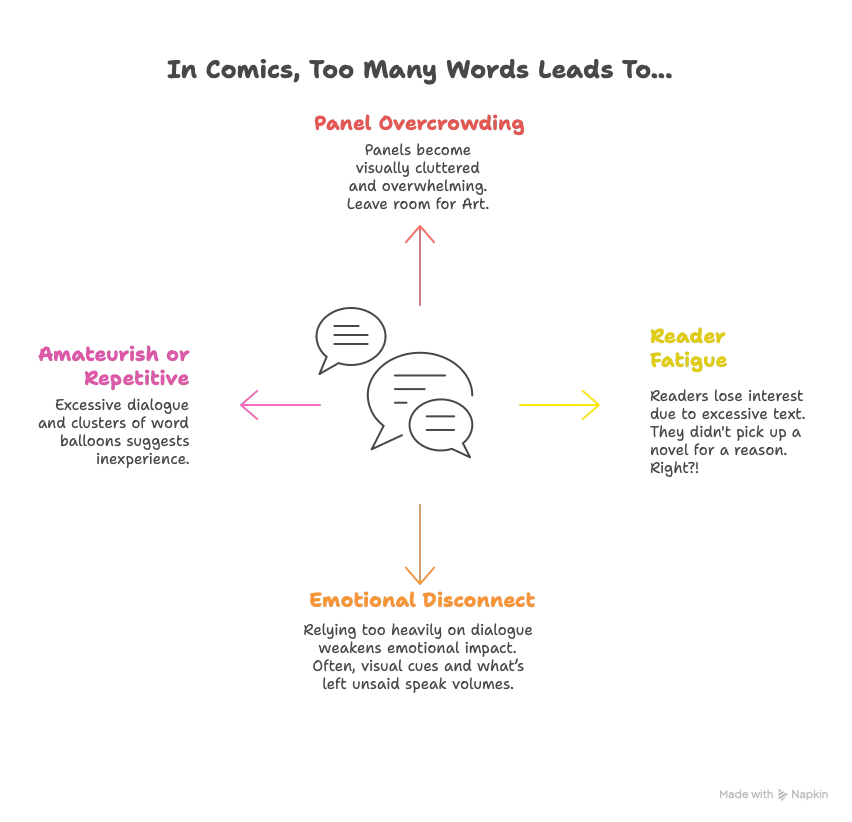

Why "Talky" Dialogue Breaks Comics

The medium has limits—spatial, visual, and cognitive:

Word balloons suck the air out of a panel if they exceed ~24 words (a best practice, not a law—but break it with caution).

Comics aren't novels. Readers scan quickly, some faster than others. Slow, internalized scenes lack emotional weight without strong visuals.

Interiority? You get a single caption or a thought balloon to go with your close-up. No monologues, no meandering thought spirals. Run-on sentences aren't great in prose, but they're deadly in comics.

Long, yap-happy exchanges read as fake, dull, or downright amateurish.

If you want your characters to feel authentic, you must slash like a poet and reveal like a screenwriter. Visuals supercharge your words.

What to Cut (and Why)

Like Strunk and White warned: "Omit needless words." But how?

Here's a practical checklist to revise your dialogue and make it sing on the comics page:

1. Slash the Filler Words

Start with this hit list:

Just, really, very, that, so, actually, kind of, like

Old-school clutter: Believe you me, if you will, needless to say

"The thing is," "You know what I mean?" and "I mean…"

The more I write, the more this trimming feels natural. I love slashing and burning all that filler; it strengthens my writing.

Example:

Before:

"I just kind of think that maybe we shouldn't go in there, you know?"

After:

"We shouldn't go in."

Fewer words = More weight.

2. Keep One Idea Per Panel

Each panel is a unit of meaning. Don't stack ideas or lines that require timing or nuance—break them into multiple panels.

Tip: If a character makes three points in one speech bubble, you likely need three panels. It's ok to have three small panels instead of one larger one.

3 distinct ideas = 3 separate panels

3. Use Sentence Fragments and Punchy Rhythm

Natural dialogue isn’t grammatically perfect—it’s direct, emotional, and raw.

Instead of long-winded exchanges, aim for short, sharp beats that mimic real speech patterns:

“You lied to me.”

“Thought you’d died.”

“One shot—make it count.”

Each line lands with precision, delivering quick emotional hits. Panels act like drumbeats, each fragment building tension through brevity, pace, and purposeful rhythm. This might make your childhood English teachers uncomfortable. Sorry, comics are a mass medium in a way novels are not, at least not anymore.

4. Let the Art Do the Talking

If the facial expression shows regret, the line doesn't need to say, "I'm sorry."

Instead:

"Didn't mean to."

"Should've told you." [Or even silence, let the pose deliver the emotion.]

Your visuals carry tone, gesture, and subtext. Trust them. Dialogue and art should dance around each other, not explain each other. Emotion is a game of subtext. What is left unsaid is often more critical than what is. Just ask any skilled therapist. I’m confident they’d support me on this.

5. Build a Style, Not a Transcription

Want authentic characters? Don't record your speech. Intensify it.

Actually, I take that back. If you want to record it, do it. It's a great way of initially capturing thoughts and dialogue. I do this in my creative process. Do what works for you. But don’t edit as you go. Save that for the next phase.

After you’ve got it down, then you ruthlessly edit what you’ve transcribed.

Teenagers don't say "verily," but they also don't need 17 "likes" in a row—even if they do in real life. The page isn't real life.

Use slang sparingly.

Use voice consistently.

6. Modulate the Voice

Not every line should land the same way. Good dialogue shifts gears—it bends and flexes tone, rhythm, and vocabulary depending on who's talking, what's at stake, and how the emotional temperature changes. Lisa Burdige called it voice modulation, which was a term I was unfamiliar with. It’s the ability to move between pressure and release, between punch and pause. She was reviewing a colleague’s story, and I trust her; she’s a more skillful writer than I am. (Thanks, Lisa. Wil and I loved meeting you at Fanfaire2025. Check out her Instagram feed, link below.)

If all your dialogue hits with the same intensity, it feels flat or forced. A drum solo with uniform punch is boring. Hit the skins with style, dude.

Ask yourself:

Do all your characters sound like they're delivering monologues in the same register, or does the rhythm shift based on mood, stakes, and identity?

Example – Unmodulated Dialogue:

Panel 1

JANE: "I can't believe you lied to me. I told you everything, and you betrayed me. I don't even know who you are anymore."

Panel 2

JANE: "You said we'd face this together. You said I could trust you. You said you'd protect me."

Everything is at the same volume. The rhythm is repetitive. There's no shift in emotional register—it's all high drama with no contrast. In art, the lack of contrast limits your compositional control. The same is true for writing.

Example – Modulated Dialogue:

Panel 1

JANE: "You lied."

Panel 2

(Beat.)

JANE: "I told you everything."

Panel 3

JANE: "And you—"

JANE: "You just stood there. Let it happen."

Panel 4

JANE (quiet): "You said you'd protect me."

Now we have variation. Bonus? It's also shorter, which jams nicely into a word balloon. Most lines are clipped. Some are longer. Some are quiet. (Tip: In comics, use a dotted line word balloon to communicate the character is whispering.) There's space for the reader to feel the shift and hear Jane's anger and hurt. That's voice modulation in action.

Great comic dialogue is a voice designed for effect, not recorded for accuracy. Four smaller panels in the same space as two don’t require additional drawing; the lines just get arranged differently. The increased tension and heightened emotions make additional panels a no-brainer.

Rule of Thumb: Write It However You Like, Then Cut by Half

When you write a draft of your dialogue, it will sound like what's in your head. Fine. If there’s anything I’ve learned, it’s that my process is my process. Other writers have their own. Embrace what gets words on the page. How you make that happen doesn’t matter. But once the words exist in tangible form, it's time to shift gears.

Now halve the words. Scalpel time. Or Scythe. Your choice, but keep the blade sharp.

After the first pass, ask: Can this be said with a look? A gesture? A pause?

Cut again. Leave the best six words. (Do I mean “six” literally? I do not. But, keep it terse.)

Steve Walker, who's been working in comics for decades, always speaks his dialogue out loud. I never used to do that. I do now. It's a great way to eliminate awkward phrasing that looks good onscreen but fails miserably in a word balloon. I say it out loud to ensure I haven’t accidentally made the phrasing weird during editing. Still, keep lines short. Brevity is better, at least for comics.

Closing Thoughts

Writing "natural" dialogue in comics means writing with intention; don't be a court reporter; be a poet. Capturing exactly how you speak and shoving it into word balloons would be like adding an aria to a novella—wrong form, wrong medium.

You're not on a wiretap, transcribing every word spoken. Leave that to the NSA.

When dialogue is tight, punchy, and visual, it feels more real than when you include every single additional extra superfluous word. Remember, comics are a partnership. Art carries half the load. That's its job. Don't get the union boss involved by messing with the electrician's power drops; things get ugly when you step on their toes. Respect each department.

Trim away.

Charles Merritt Houghton

10 May 2025

Check out Lisa and John's fabulous work on Instagram at

https://www.instagram.com/background_noise_comic/